Description & Other Names

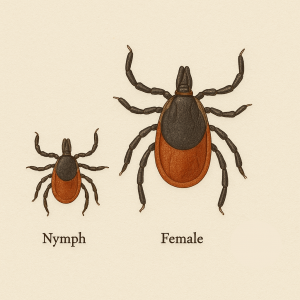

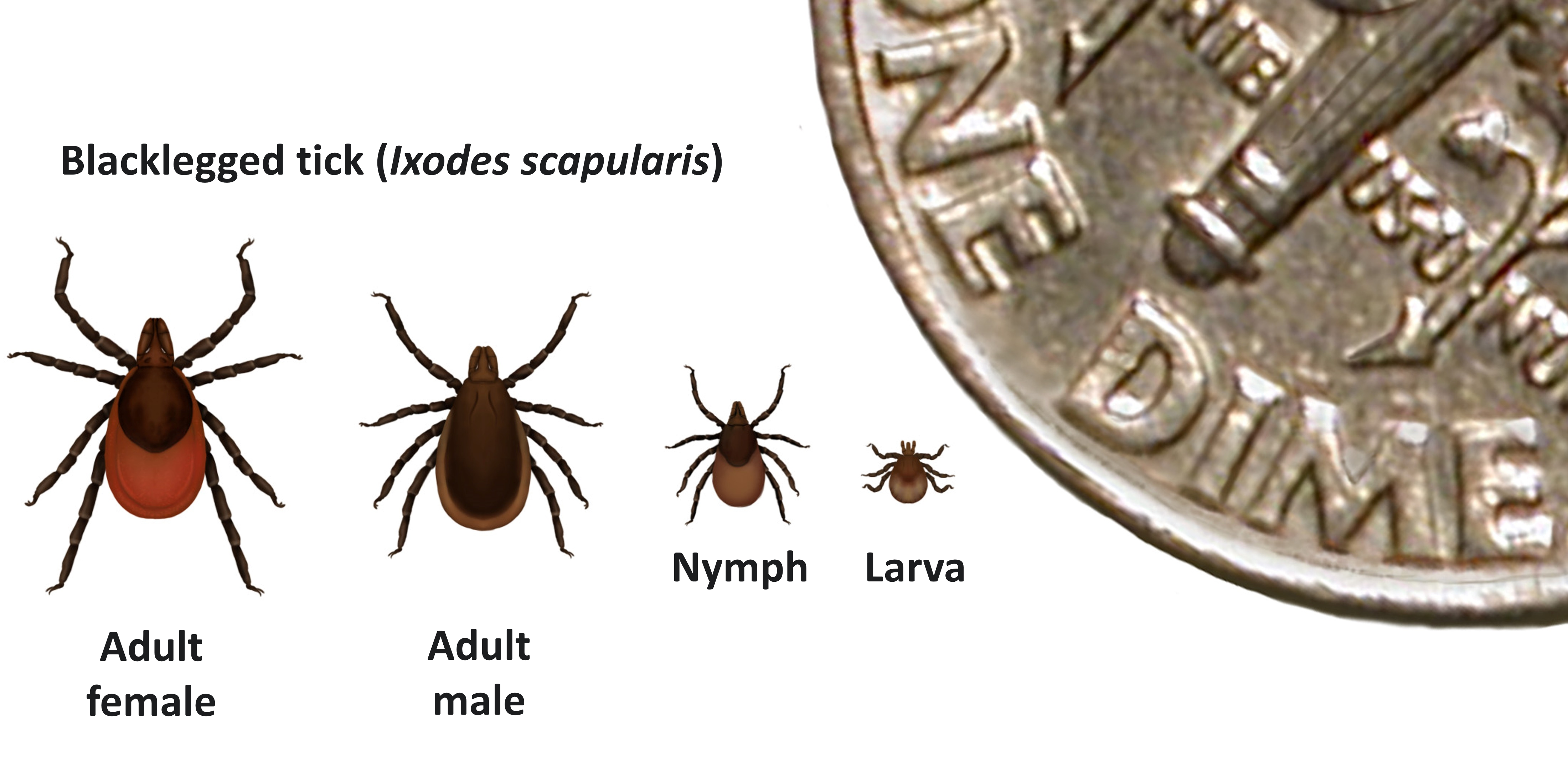

The blacklegged tick is often called the deer tick because deer are one of its favorite hosts (especially for adult ticks). Scientifically, it’s Ixodes scapularis. These ticks are small (among the smallest hard ticks). Adults are about the size of a sesame seed (just a few millimeters) and nymphs (the stage most likely to bite you) are as tiny as a poppy seed. They have black or dark brown legs (hence “blacklegged”). Adult females have a two-tone appearance: a reddish-orange brown body with a black shield (scutum) near the head, and black legs. Males are smaller and dark brown overall. Because of their small size, they can be hard to spot on your body, especially in hair.

Where Found

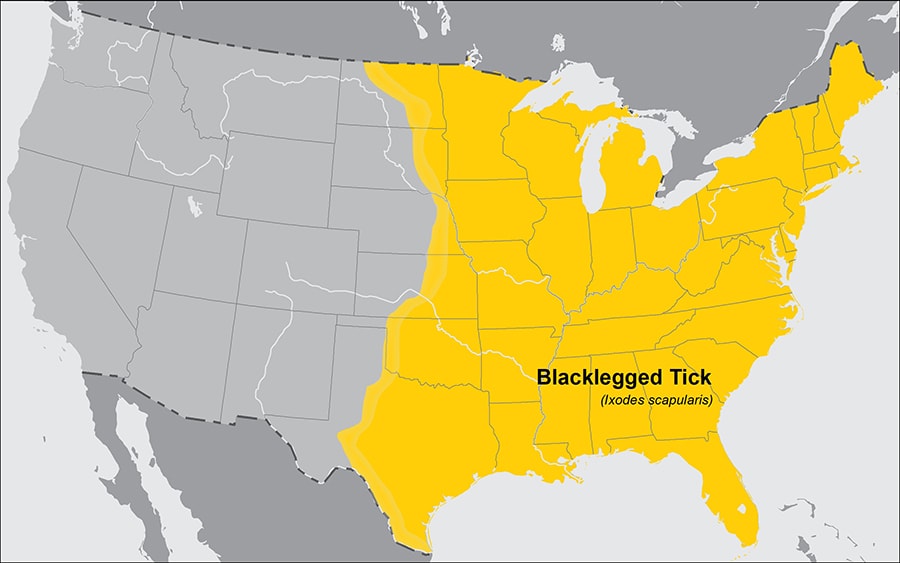

Blacklegged ticks are found widely in the Eastern United States – basically the entire eastern half of the country from the Plains to the Atlantic. They are especially abundant in the Northeast (New England, Mid-Atlantic) and the Upper Midwest (Wisconsin, Minnesota, Michigan). They thrive in wooded areas, leaf litter, and edges of forests. If you looked at a map, you’d color in most counties from Virginia north through Maine, and west through the Great Lakes states, as having blacklegged ticks. They are not naturally found in large numbers in the far south (e.g., not much in Florida’s hot climate, and in much of the Deep South, though some pockets exist). There is a Western blacklegged tick (Ixodes pacificus) on the Pacific Coast (California, Oregon, Washington) that is a close cousin and plays a similar role there. So essentially, if you’re anywhere in the U.S. except the Rocky Mountain area or far south Texas/Florida, assume deer ticks could be around.

Diseases Spread

The blacklegged tick is the big villain in terms of disease transmission. It can carry a whole rogues’ gallery of pathogens:

- Lyme disease (Borrelia burgdorferi and Borrelia mayonii)

- Anaplasmosis (Anaplasma phagocytophilum)

- Babesiosis (Babesia microti parasite)

- Powassan virus, and even a form of

- Ehrlichiosis (Ehrlichia muris eauclairensis in the upper Midwest).

They can also transmit Borrelia miyamotoi (which causes a type of relapsing fever).

In short, if a blacklegged tick bites you, there are several things you have to be on guard for. Lyme is by far the most common. Often these ticks are carrying more than one bug, which is why co-infections (like getting Lyme and Babesia together) can happen.

So deer ticks are tiny but mighty dangerous! They’re responsible for the vast majority of tick-borne disease cases each year in the U.S.

Active Season

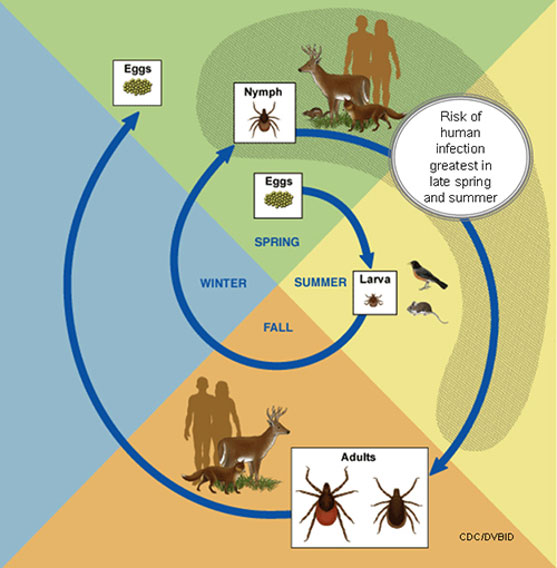

Blacklegged ticks have a 2-3 year life cycle. They are active pretty much any time the temperature is above freezing, but they have peak seasons. Nymphs (the young stage) are most active in late spring and summer (May through July). And nymphs cause most Lyme cases because they’re so small and often go unnoticed. Adult ticks are active in spring and fall (you often see an uptick in Lyme in October/November from adult bites). Adults can even be out in winter on mild days (if it’s, say, 40°F and sunny, they can quest). The highest risk of being bitten is in spring, summer, and fall, indeed. They tend to lurk in leaf litter and low vegetation, crawling up on grasses or shrubs and waiting for a host (like you) to brush by. They do not jump or fly. They wait with legs outstretched (a behavior called “questing”) to grab on.

How to Identify

Size is a big clue. These are smaller than the other common ticks. If you find a really tiny tick, especially attached to skin, it’s likely a deer tick nymph. The adult female’s appearance (orange-brown body with a black shield behind the head) is characteristic (compared to, say, dog ticks which have more ornate white patterns). Deer ticks also have black legs, whereas something like the Lone Star tick has brownish legs. An engorged deer tick (after feeding) can balloon up and look grayish-blue and much larger, which can make identification tricky. But if it was tiny before feeding, think deer tick.

Another tip: deer ticks are in the Ixodes genus, which have no ornamentation on their backs (unlike dog ticks and Gulf Coast ticks which have white/silver markings). Also, Ixodes ticks have a more elongated mouthpart you can sometimes notice. If you’re not sure, you can take a clear photo and compare to images on our or any other site. When in doubt, assume deer tick if in a deer tick region, and treat it seriously in terms of monitoring for Lyme symptoms.