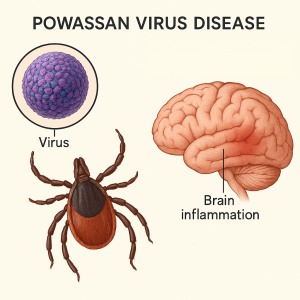

Cause & Spread

Powassan virus disease (often just called “Powassan” for short) is one of the few tick-borne viruses in the U.S. (most other tick illnesses are bacteria or parasites). It’s rare, but it’s been in the news more as cases have increased in recent years. Powassan virus is named after Powassan, Ontario, where it was first identified. There are actually two types of Powassan virus strains (lineages 1 and 2), one of which is sometimes called “deer tick virus”, but both cause similar illness. Powassan virus is primarily spread by ticks, especially the blacklegged tick (deer tick) and a related tick called the groundhog tick (Ixodes cookei). Basically, the same deer ticks that transmit Lyme in the Northeast can carry Powassan virus (though it’s much more rare). Ticks get the virus by feeding on small animals like woodchucks (groundhogs), squirrels, or mice that have the virus, and then the tick can transmit it to humans. Powassan virus is found in the eastern half of the United States, mainly in the Northeast and Great Lakes areas. Unlike Lyme bacteria which typically needs a tick attached for >24 hours, Powassan virus can be transmitted in a shorter feeding time (even as little as 15 minutes in animal studies). People do not transmit Powassan to each other (it’s not like the flu), except in the very rare case of blood transfusions (hospitals ask donors about Powassan and other infections to be safe). Unfortunately, because it’s a virus, there’s no specific medicine to kill Powassan virus once you’re infected. This is why preventing tick bites is extra important for this one.

Regions at Risk

Powassan cases are still quite uncommon. Only a few dozen cases are reported in the U.S. most years. But they have been rising. Most cases have been reported from Northeastern states and the Great Lakes region (Upper Midwest). States that have reported cases include Minnesota, Wisconsin, New York, Massachusetts, New Jersey, Maine, New Hampshire, and Pennsylvania, among others. These are generally the same areas where Lyme is common, which makes sense given the tick involved. Powassan virus tends to be transmitted in late spring, through summer, into early fall (May to October) when ticks are active. Unlike Lyme, which can be cured and usually doesn’t kill people, Powassan, while rarer, can be very serious. So it’s something on the radar in those high-risk regions. All it takes is one unlucky tick bite. So if you’re in, say, rural New England or Wisconsin and get tick bites, Powassan is a low possibility but a concerning one.

Symptoms

The majority of people who get infected with Powassan virus actually never develop symptoms (maybe around 70-80% asymptomatic). The unlucky ones who do get sick will typically show symptoms anywhere from 1 week to 1 month after the tick bite. Early symptoms are usually generic: fever, headache, vomiting, and weakness. This can then progress to very serious problems: Powassan virus has a predilection for the central nervous system, meaning it often causes encephalitis (inflammation of the brain) or meningitis (inflammation of the membranes around the brain and spinal cord). Signs of severe disease include confusion, loss of coordination, difficulty speaking, and seizures. Essentially, it can cause the brain to swell, which is life-threatening. About 1 in 10 people with severe Powassan disease die, and roughly half of the survivors of severe disease are left with long-term problems. These long-term issues can be things like chronic headaches, muscle wasting and weakness, memory problems, or other neurological deficits. It’s one of those viruses that if it hits the brain hard, recovery can be a slow and incomplete process. Obviously, these stats only apply to those who get the severe neuroinvasive disease. Many infections are asymptomatic or mild. But because we can’t predict who will get very sick, every case is taken very seriously.

Diagnosis

If Powassan is suspected (for example, someone in an endemic area develops encephalitis in summer), doctors can diagnose it with lab tests. Typically, they look for antibodies against Powassan virus in the blood or spinal fluid (from a lumbar puncture). There’s also PCR tests for the virus, but since the virus may not be in the blood by the time of symptoms, antibody tests are more common. Often they test for a panel of arboviruses (like West Nile virus, another encephalitis virus) to pin down the cause of brain inflammation. It’s not an everyday test and these samples might be sent to specialized labs or the CDC.

Treatment

There is no specific antiviral treatment for Powassan virus. That means we don’t have a pill or shot that targets this virus specifically. So the treatment is “supportive,” which means doctors try to support the patient’s body and manage complications while the person’s immune system fights off the infection. Severe cases often require hospitalization. Sometimes in the intensive care unit. Treatments may include: rest, fluids, and over-the-counter pain relievers for mild cases. For severe cases, patients might need help with breathing (a ventilator if they can’t breathe well on their own due to brain dysfunction), IV fluids, and medicines to reduce brain swelling, such as corticosteroids or other interventions. They will also treat any secondary issues like seizures. It’s basically meticulous medical care to keep the person alive and prevent further damage while their body fights the virus. Recovery can take a long time, and some people may need rehabilitation therapy after (physical therapy, speech therapy, etc., depending on what deficits they have). Prevention is absolutely key with Powassan: avoid tick bites! Because unlike Lyme, you can’t just take antibiotics to try to fix it. Also, there’s no vaccine for Powassan for humans (research is ongoing). The silver lining is that Powassan is rare. But if you’re in a risk area, you should definitely use tick precautions (we cover those on the Prevention page!).