Fun Fact

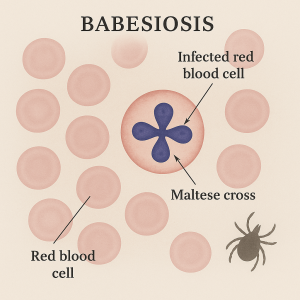

A lab can look at a blood sample under a microscope to actually see the Babesia parasites inside red blood cells. They sometimes form a cross shape inside the cell, called a “Maltese cross” (cool but also not cool because, you know, bad parasites).

Cause & Spread

Babesiosis is caused by a tiny parasite (a so-called protozoa) that infects red blood cells. This is sort of like a tick-borne cousin of malaria. The main culprit in the U.S. is Babesia microti. You catch babesiosis through the bite of an infected blacklegged tick (deer tick) – the same tick that transmits Lyme disease. Often, the tick is in its nymph stage (the size of a poppy seed) when it gives you Babesia parasites, meaning it’s super-easy to miss. Ticks pick up Babesia by biting infected small animals (like mice) and then can pass it to humans. Babesiosis cases tend to peak in the warmer months, especially late spring and summer, when young ticks are active. Rarely, babesiosis can also be transmitted through a contaminated blood transfusion or from mother to baby during pregnancy, but tick bites are by far the most common route.

Regions at Risk

Where does this happen? Mostly in the Northeastern and Upper Midwestern U.S. (the same areas known for Lyme, which makes sense since it’s the same tick). In the Northeast, Babesiosis is common in New England (e.g., Massachusetts, Connecticut, Rhode Island) and New York (especially Long Island and the islands like Nantucket and Martha’s Vineyard).

Symptoms

Good news (sort of): many people with Babesia infection don’t feel sick at all and never know they had it. Their immune system quietly handles it. However, some people do get sick, and the illness can range from mild to life-threatening. Symptoms usually start 1-4 weeks after the tick bite (so a bit longer incubation than Lyme). When symptoms occur, they often start like a summer flu: fever, chills, sweats, headache, body aches, loss of appetite, nausea, and fatigue. No rash with babesiosis (that’s more a Lyme or maybe RMSF thing). Because the Babesia parasite infects red blood cells, it can cause those cells to burst, leading to hemolytic anemia (anemia from destroyed blood cells). Signs of this can include jaundice (yellowing of the skin or eyes) and dark tea-colored urine. Most otherwise-healthy people will either have no symptoms or a mild illness that they recover from. But babesiosis can be severe, especially for people who are older, who do not have a spleen (the spleen is an organ that helps filter blood, and without it it’s harder to clear the infection), or who have weak immune systems (for example, due to cancer, HIV, or certain medications). In severe cases, babesiosis can cause very low blood pressure, severe anemia, organ failure (kidneys, lungs, liver), and it can be life-threatening if not treated.

Diagnosis

If someone has been in a tick area and comes down with an unexplained summer flu or anemia, doctors might suspect babesiosis (especially in known hotspots like coastal New England). The diagnosis is often made by a blood test. A lab can look at a blood sample under a microscope to actually see the Babesia parasites inside red blood cells (they sometimes form a cross shape inside the cell, called a “Maltese cross” – cool but also not cool because, you know, parasites). There are also blood antibody tests and PCR tests (which look for Babesia DNA) to detect the infection. Sometimes babesiosis is found when testing for Lyme or other tick diseases. Doctors might run a panel of tests if you have nonspecific symptoms.

Treatment

Babesiosis is treatable with anti-parasitic medication. Since Babesia is not a bacteria, the usual antibiotics for Lyme won’t cure it. It needs specific meds to kill the parasite. The standard treatment for symptomatic babesiosis is a combination of two prescription medications for 7–10 days: typically atovaquone (an antiparasitic drug) plus azithromycin (an antibiotic). In more severe cases, a stronger combo of clindamycin + quinine may be used. People who are asymptomatic usually don’t need any treatment at all (the infection may clear on its own). Patients who have a compromised immune system might need to be treated for a longer period to fully clear the parasite. With treatment, most folks improve within days, but it’s important to finish all medicine. In very severe babesiosis (like if someone has a heavy parasite load in their blood causing organ failure), exchange blood transfusions have been used (that’s where they slowly replace a patient’s blood with fresh donor blood to literally remove the infected blood cells). That’s only in extreme cases, though.

Bottom line: If you get babesiosis, there are effective treatments available, and the earlier you get treated the better.