Cause & Spread

Anaplasmosis is caused by another type of bacteria that is a cousin of Ehrlichia, called Anaplasma phagocytophilum. It used to be called “human granulocytic ehrlichiosis” until they reclassified it. But you can just call it anaplasmosis (ann-uh-plaz-MO-sis). Like ehrlichiosis, these bacteria live inside your white blood cells. The disease is spread by the bite of infected ticks, mainly the blacklegged tick (deer tick) in the East and upper Midwest, and the western blacklegged tick on the Pacific Coast. So the tick vectors for anaplasmosis are the same ones that cause Lyme disease. In fact, these ticks often carry multiple germs, so co-infection can occur (meaning you could get Lyme and anaplasmosis from the same tick bite; unlucky, but it happens). The range of anaplasmosis is expanding, and cases have been rising, likely because ticks are expanding their range. Like other tick diseases, it’s more common in late spring and summer (when nymph ticks feed, and people are outdoors), but can occur into the fall. Rarely, anaplasmosis has been transmitted by blood transfusion as well, since the bacteria can live in blood, but that’s unusual.

Regions at Risk

In the eastern U.S., the blacklegged tick spreads Anaplasma, and in Northern California and the West Coast, the western blacklegged tick spreads it. Anaplasmosis is most common in the Northeastern and Upper Midwestern states: states like New York, Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Jersey, Wisconsin, Minnesota. This is very similar to the Lyme’s distribution.

Symptoms

Anaplasmosis typically starts 5-14 days after the tick bite (so about a week, similar to ehrlichiosis). Its symptoms are a lot like ehrlichiosis: fever, severe headache, muscle aches, chills, and feeling very tired/malaise. Some people also get nausea, abdominal pain, or less commonly cough. One big difference: a rash is very uncommon in anaplasmosis. If someone has a rash, it’s likely not anaplasmosis (or they have a co-infection like Lyme). So think of anaplasmosis as “flu in the summer without a rash.” Many cases are mild. In fact, some people might have anaplasmosis and never realize it or just think they have a viral illness. However, it can be severe, especially if not treated early. Complications can include difficulty breathing, bleeding problems, or organ failure in rare cases. The good news is that fatal outcomes are rare (less than 1% of reported cases). Still, older individuals or those with compromised immune systems are at higher risk for severe illness.

Diagnosis

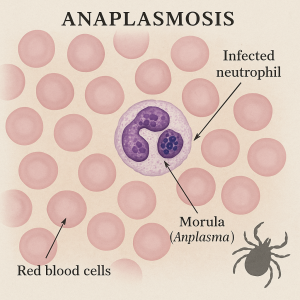

Diagnosing anaplasmosis can be tricky because it’s not as famous as Lyme and it doesn’t have a telltale rash. Doctors will consider it if you have a tick exposure and compatible symptoms. Lab tests: a PCR test can detect the DNA of Anaplasma in your blood (especially in the first week of illness). There’s also an antibody test, but that usually only turns positive in the second week or later, so it’s more for confirmation. Often, diagnosis is clinical (meaning if you’ve got a July fever and headache and you live in, say, Wisconsin, the doc might just treat for anaplasmosis – and ehrlichiosis and Lyme – while awaiting results). On a blood smear, sometimes the lab can actually see Anaplasma inside white blood cells (they form little clumps called “morulae” in the granulocytes), but this is not always seen. Routine blood counts may show low platelets or low white cell count, similar to ehrlichiosis.

Treatment

Doxycycline is the hero again here. Just as with ehrlichiosis (and RMSF), doxycycline is the recommended and most effective treatment for anaplasmosis. You treat anaplasmosis with doxycycline for about 10-14 days typically, to cover possible co-infection with Lyme (Lyme requires a longer course than anaplasmosis would on its own). The duration might vary, but often 10 days of doxy is prescribed, which also conveniently would treat early Lyme if present. As with other rickettsial diseases (diseases from bacteria of the order Rickettsiales: Rickettsia, Ehrlichia, and Anaplasma among others), starting treatment early is crucial to prevent complications. Fortunately, anaplasmosis responds quickly to doxycycline. Patients often feel a lot better within 48 hours of starting meds. There’s no effective alternative antibiotic (rifampin can be used in those who absolutely cannot take doxy, such as pregnant women, but that’s a special scenario). There’s no vaccine for anaplasmosis, so prevention is key.

Bottom line: If you get a summer flu and live in an area with anaplasmosis, see a doctor and mention tick exposure. A simple course of antibiotics can fix you up quickly. Don’t tough out a fever thinking “it’s just a virus” if it could be a tick thing!